If you want to start cooking Japanese food at home, all you need is five basic ingredients, shoyu, mirin, sake, miso and dashi. These five form the basic building blocks for Japanese flavour. With it, you can make miso soup, sukiyaki, shabu shabu, tempura, udon, teriyaki, yakitori, oyakodon and many other popular dishes.

So, if Japanese cooking is such a “Simple Art” as Shizuo Tsuji states in the title of his seminal cookbook “Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art”, then how is it that the food served at the top end restaurant tastes so much better than what we can cook at home?

Well, the devil as they say, is in the details. If you visit a Japanese supermarket, you will be amazed at how many types of shoyu and miso there actually are and each recipe actually calls for a very specific type! But perhaps the one thing that makes the biggest difference to the food served at restaurants and what you try to cook at home is the quality of the dashi or basic stock.

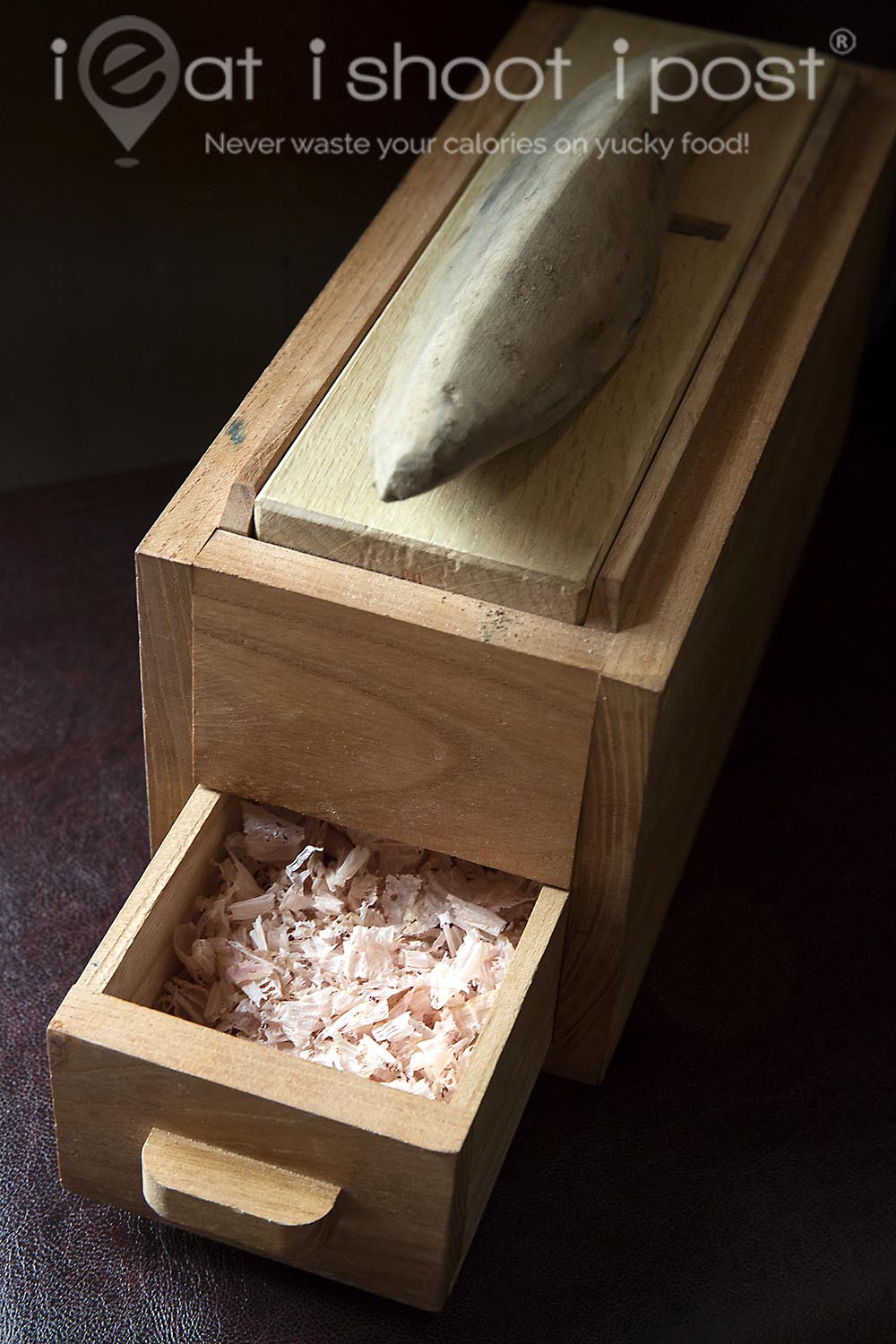

Dashi is the engine that drives the umami in soups, sauces and braised dishes. Most home cooks would rely on hon-dashi which is a granulated powder which you simply add to water to get instant dashi. Restaurants on the other hand would make their own dashi everyday and the quality of their kombu (kelp) and katsuobushi (bonito flakes) will determine the umami power of their basic dashi. The really good restaurants will boast that they use only wild Rishiri kombu harvested from the frigid waters of Northern Hokkaido and two year old, cured katsuobushi. The super top end restaurants might go one step further and import water from a certain well and shave their katsuobushi ala minute to make the dashi!

Marusaya’s key selling point is that they are a wholesaler for katsuobushi so they are able to use the top quality katsuobushi in their restaurant to make their dashi. That is why they are bold enough to call their restaurant “Dashi Master”!

There are generally two types of katsuobushi. Karebushi is the traditional type that is made with a mold that is applied to the surface of the bonito blocks after they have been smoked and dried. Most of the shaved kezuri-bushi (bonito flakes) you find at the supermarkets are made from arabushi (aka hadakabushi) which are produced with a shorter process that takes about 1 month to complete. Arabushi has a strong smokey aroma and a fishy flavour unlike karebushi which is clean tasting provides maximum umami punch without its own flavour to steal the limelight from the key ingredient in the dish.

The restaurant uses Satsuma hongare-honbushi which has been aged for two years. The normal process for producing karebushi is around three to six months. During this time, the bonito are filleted, then poached in water for an hour after which the bones are removed. Then they undergo three weeks of smoking and drying. At the end of this process, you get arabushi which is the lowest grade of katsuobushi. To make karebushi, a mold called aspergillus glaucus is applied to its surface and the mold is cultivated for a period of time before being sun dried. This cycle of cultivation and sun-drying is then repeated several times over the period of curing. The mold accelerates the drying of the katsuobushi, concentrating the umami and decomposing the fat to give the katsuobushi a clean, yet sophisticated flavour. To make the special two year old Satsuma katsuobushi, the molding and drying process is stretched over a two year period which result in a complexity of flavours that only time can produce.

Katsuobushi is at its most fragrant when it is just shaved. The very best chefs in Japan should always insist on manually shaving their katsuobushi just before making dashi. But this is a time consuming task, so many chefs have their katsuobushi freshly shaved and delivered to their restaurant instead. Chef Akane told me that their katsuobushi was shaved by hand when they first started business. The service staff had to take turns shaving katsuobushi in between services! But as the business grew, they eventually invested in a special machine to do the work.

With that primer on dashi, let’s get down to the food.

What impresses me about Marusaya is its insistence on using only all natural ingredients in its cooking. They usually have four different dashi in the kitchen which are made in-house. Aside from the basic dashi that is made from kombu and bonito flakes, they also use other dried seafood like niboshi (ikan bilis/anchovies) and sababoshi (cured mackeral) to make the dashi for different dishes.

They have just launched a series of lunch sets which I feel are excellent value especially when you take into consideration the quality of the ingredients being used. The sukiyaki udon set is comes with a large bowl of freshly made udon and a clear soup that is made with the aforementioned dashi and topped with freshly shaved bonito flakes. The set even comes with onigiri, potato salad, pickles and dessert! 4.5/5

The tendon set is also excellent value. It includes a bowl of cold udon, salad, pickles, soup and dessert for $19. I found the sauce for the tendon a little on the sweet side and would have preferred it to be a little more savoury. Otherwise, the tempura batter is light and crisp and the Japanese rice is excellent. 4.25/5

Lots of places can make a decent tempura. The batter is quite straightforward and as long as the oil temperature is well controlled you should get a nice, crispy lacy crust. However, when it comes to the dipping sauce, not everyone will be able to boast about it being made from all natural ingredients. Mass market tempura places usually make their dipping sauce by opening a tetra-pak, adding water and heating it up. These pre-packed sauces are readily available and can be quite tasty but usually will have preservatives and other flavour enhancers added.

At Marusaya, the dipping sauce is made from the basic katsuobushi and kombu dashi to which sababushi (dried mackeral fillets) is added for extra flavour. Sababushi is made from gomasaba (spotted mackeral) and the fish is quite fatty which produces a rich fishy flavour that goes really well with the tempura. 4.25/5

Mushrooms work really well as tempura. I like the maitake (舞茸) mushroom tempura which has a very unique flavour. They also have matsutake mushrooms which is highly prized by the Japanese. It is supposed to be their equivalent of truffles! I have tried matsutake several times and personally haven’t found them to be as seductive as white truffles.

One of the simplest ways of enjoying the dashi flavour is to use it to fry an omelette. This is eaten with some grated daikon and katsuobushi flavoured shoyu or with their special umami powder made from powdered katsuobushi. It is deceptively simple but supremely satisfying! 4.25/5

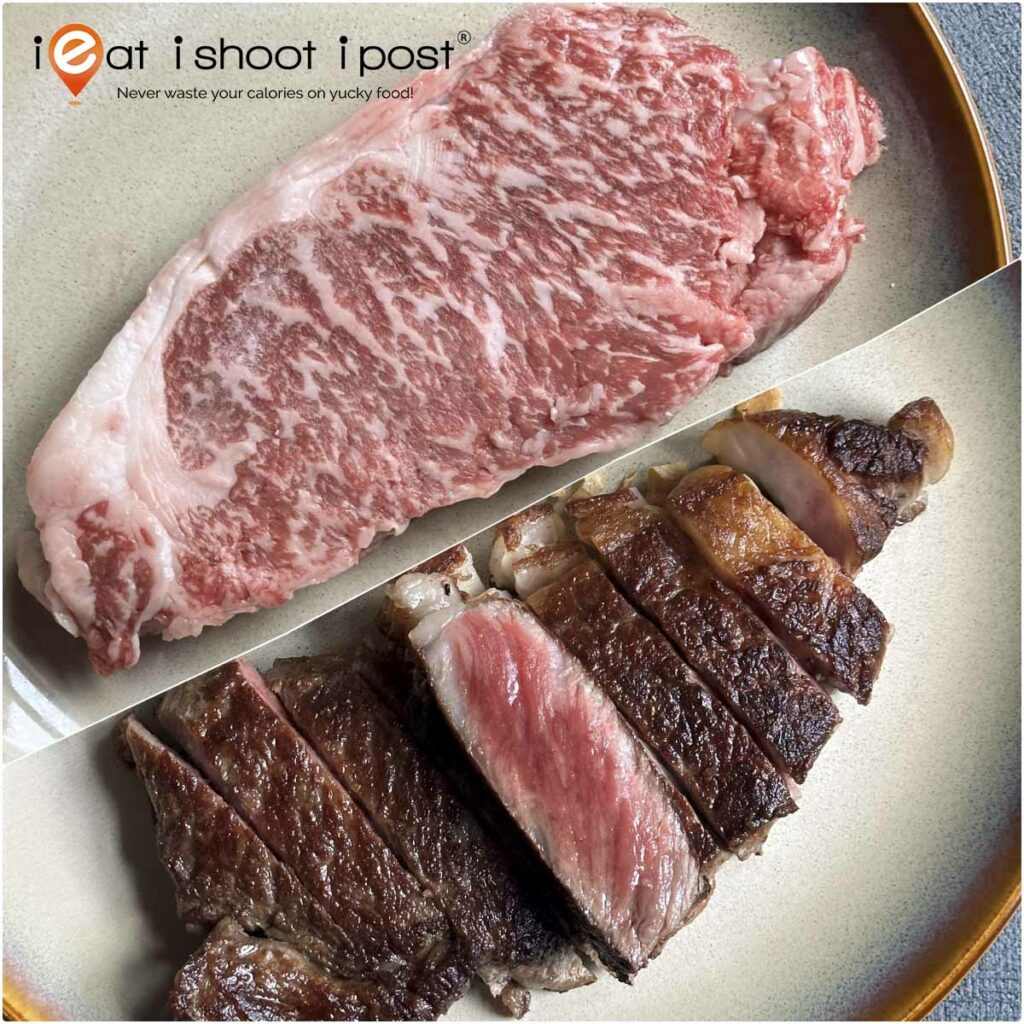

The ultimate way to enjoy their dashi is to go for their Shabu Shabu. This is the first time I have come across a Shabu Shabu where more emphasis is placed on the soup than the meats! The meat is a given, they use A5 Miyazaki Wagyu sirloin which sublime but what adds the extra punch is their excellent soup base which is made fresh at your table. If you have tried to make dashi at home, you would know that the ingredients for the soup base would already cost $20 if you buy your ingredients from the supermarket! The dipping sauces are also all made in-house by Chef Akane. Excellent shabu shabu experience. 4.5/5

Conclusion

Restaurants like Dashi Master Marusaya are really understated. Some casual diners might find the flavours too subtle but for fans of Japanese cuisine, Marusaya is a welcome addition to Singapore’s increasingly authentic Japanese food scene.

It should be noted that dashi is most commonly made from KB and K, but(!) there are many different kinds of dashi in and of themselves. Some are just kombu, while others can use a variety of dried seafood products like squid, anchovies (niboshii) or even mollusks. // This place looks amazing and I am jealous. There is nothing like it here in South Korea.